|

Art and Existentialism

© Robert

Foddering 1998

Part I: Art and Existentialism

Aims

Introduction

Existentialism

Art and Existentialism

Investigative Problems

Tate :Paris Post War: Art and Existentialism

1945-55

The Artists

Commonality

Further Study

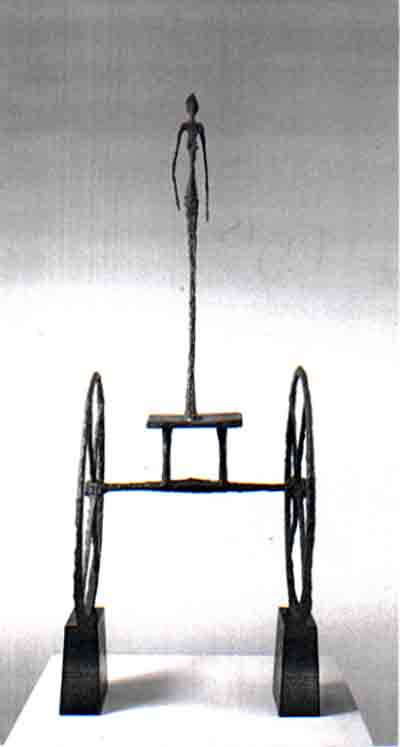

Giacometti

Part II: Giacometti and

Existentialism

Introduction

Giacometti

Giacometti’s Concerns

Giacometti’s Work

Giacometti and Existentialism

Part

III: Art and Perception- Existentialism?

Introduction

Existentialism and Contemporary

Influence

Cezanne to Arikha- Existential Perception

Not Limited To Existentialism

Existentialism and Perception

Conclusion

Bibliography

List Of illustrations

|

Part I - Art and Existentialism |

“What expresses

itself in language,

we cannot express

by means of a language. What can be shown, cannot be

said.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein,

Tractatus

Part I - ART

AND EXISTENTIALISM

Aims

Existentialism holds

a personal interest for me, especially in its attempts

to explain mans existence within the world. I feel that

existentialism and its expression within the arts, reflects

closely with the interests I have developed in my personal

work and perhaps its concerns are still relevant to

all artists operating in contemporary society.

Throughout this dissertation

I aim to investigate the commonality between the philosophy

of existentialism and the production of the arts. This

will lead to an investigation into the method of genuinely

representing existence within art. There should be investigations

into the artist and their work. Areas that delve into

the relationship between a philosophy and the arts and

how genuine that relationship is. This allows us to

investigate how deeply society, contemporary thinking

and mood affect individual artists and whether a philosophy

can truly be represented or used as a motivation for

production within the arts.

Introduction

Existentialism was

a philosophy that developed during the occupation and

the French post-war period of 1945. It was a time of

great change, the aftermath and atrocities of the Second

World War left Europe’s, and perhaps the entire

world’s population re-evaluating the meaning of

their existence. At the same time being confronted by

nuclear threat, death and mass destruction.

“World war

two constituted a natural disaster, in so far as it

tore asunder the seamless web of signs that constitutes

modern civilization. Philosophy and art should simply

be about the possible actions and decisions a human

being who is stripped of his role can take.” 1

In the post-war period

existentialism filtered through to all areas of main

line contemporary thinking, and a common concern for

explaining the place of man within the sphere of things

developed. Jean-Paul Sartre (the philosophy’s

greatest exponent) took the texts of Soren Kierkergaard

and Martin Heidegger and re-evaluated and added to a

contemporary philosophy of existentialism. Other existentialists

include Genet, Camus, Beckett, Ponge, Ponty and Simone

de Beauvoir (partner of Sartre.) Beauvoir defined existentialism’s

appeal to the French Post-war society:

“The masses

had lost their faith in peace, in progress, they had

discovered history in its most terrible form, they needed

an ideology which would include such relationships without

forcing them to jettison their old excuses. Existentialism

forced them to accept their transitory condition without

renouncing a certain absolute, to face horror and absurdity

whilst still retaining their human dignity, to preserve

their individuality.” 2

The post war climate

introduced a new and devastating dimension for the individual

and world politics:

”The first

half of the century ended at Hiroshima, the second half

began with gravest doubts about the human species being

around to record its end.”3

The two halves of the century also

mirrored a division in the French arts. Before the war

surrealism was the popular mode of expression, but the

occupation soon changed this, after the liberation,

the call to begin again was embodied both in existential

literature and the arts. This call perhaps overpowered

the continuation of previous debates. It was a new beginning

with

“Everything essential

still left to be defined.” 4

Existentialism

Existentialism is a

complex philosophy; in its time it was perhaps

“A climate

of opinion rather than a coherent philosophy.”

5

This was largely due

to the many different facets of the philosophy that

refused definition in a brief text. Sartre’s first

existential text “Being and Nothingness”

was published in 1943 and it was read for a decade after

this date.

“For those

dauntless enough to take on the work, a healthy amount

of time was needed to wrestle the beast into submission

and digest something of what is purported to offer in

the way of contemporary wisdom.” 6

This excerpt describes

the complexity of coming to terms with existentialism

and it questions the true depth any individual can achieve

in exploring existentialism through the use of a text.

Sartre followed the

650-page text with a discussion entitled “Existentialism

and Humanism” that perhaps defined the text in

an easier mode of discussion. It is essential at this

point to tackle some of the key points of existentialism,

not only to get a flavour of the philosophy, but so

that we can also evaluate the extent of which existentialism

influenced the artists we shall study.

Sartre’s existentialism

was devoid of religion and god. His explanation (Or

replacement) for the absence of a higher creator was

the term

“Existence

precedes essence.” 7

Sartre made no attempt

to explain the meaning of man’s existence, however

he provided an alternate solution to man’s questioning

of the origin of his creation. The post war period was

a time of evaluation in every mode of belief. For many,

religion did not encompass the answers society needed

considering such atrocities. The importance of political

alignment became crucial. Existentialism’s ideas

about the self-governing individual compared directly

to the socialist ideas of communism. During the post

war era Sartre became more and more aligned to the communist

ideal, this questioned his motives contained within

his texts, it also puts a shadow of doubt on his relation

to art:

“Sartre’s

alignment with the French communist party involved disturbing

silences in regard to previous editorial exposes of

Soviet labour camps and the communist party position

on art, the strict social realist campaign.” 8

The centre of Sartre’s

existentialism lay in the phrase “Existence precedes

essence,” it means that we exist before we are

consciously aware that we are alive. We then achieve

the realisation that we exist and define ourselves subsequently,

perhaps searching for the meaning of our existence at

this point, and falling short of an adequate explanation.

Sartre described it

as:

“Man first

exists, encounters himself then surges up in the world

and defines himself afterward.” 9

This countered the existence

of god, the heart of Sartre’s argument lies in

man’s need for an explanation to existence that

was consumed but not explained by the belief in god.

Sartre explained there is not a higher entity that has

created us, as we would create an object, we just simply

exist then need to explain that existence. This assumption

left society without the constraining elements of religion

and damnation. Would it be a place without positive

constraint, morality and a law-abiding civilisation?

Sartre’s answer to this was

“If existence

is prior to essence, then existentialism puts every

man in possession of himself and places the entire responsibility

for his existence upon his shoulders. He is not just

responsible for himself, but responsible for all men.”

10

This notion attempted

to place the concept of man being totally responsible

for himself and controlling his future with constant

regard to the future of society. This was perhaps a

calculated thought (And perhaps idealistic) considering

the consuming guilt of the war, if every man took responsibility

for their actions, instead of answering to a higher

command, would there have even been a war? With this

responsibility one should fashion ones own existence,

as you believe man ought to be, making a commitment

on behalf of mankind.

“There is

no reality except in action. Man is nothing else but

what he purposes, he exists only in so far as he realises

himself, he is therefore nothing else but the sum of

his actions, nothing else but what his life is.”

11

This reinforces Sartre’s

notion of man being totally responsible for himself.

If man does not attempt to achieve the things that he

should, then there is no proof of his existence and

he has failed to give his individual life meaning, which

is every mans need and desire.

Art and Existentialism

How do these points

of existentialism relate so closely to the production

of the arts? If we summarise the main points of existentialism

in relation to the practice of the artist, we shall

see that there is quite a close relationship between

the two.

“Man’s

consciousness is subjective and can never become aware

of itself objectively, except through the gaze of the

‘Other’. If other people function as mirrors,

so too can the work of art” 12

This is Sartre’s

position on the use of the artwork in existential terms.

He has placed great importance to the practical ‘use’

of art to society. However, the broader relationship

to existentialism is not as simple.

It puts every man in

control of his life, shaping himself as he wishes society

to be, the artist standing before a blank canvas has

the opportunity to completely control a portion of the

output of his existence more than any other individual.

The objects he creates are contributions to the culture

of society, and with his art he is attempting to shape

society in the fashion he sees fit. “There is

no reality except in action”, speaks directly

to the artist, assuring him that unless you create what

you should there is no justification to your existence.

Existentialism’s relation to art from these terms

seems to be through the definitive use of art to benefit

society. It is art’s benefit to existentialism

that raises doubts about genuine motives.

The individual is nothing

but the sum of his actions:

“This does

not imply that an artist is to be judged solely by his

works of art, for a thousand other things contribute

no less to his definition as a man.” 13

Sartre says that man

is judged by everything that he does not just his individual

actions. However, it’s Sartre’s use of the

artist as an example of the strongest form of an individual

representing their actions that depicts the artist in

such a strong light in comparison to the ideology of

existentialism.

“Does anyone

ever reproach an artist when he paints a picture for

not following rules a priori? As everyone knows there

is no predefined picture for him to make.” 14

This quote shows us

how Sartre related the artist to the essence of existential

ideals- “existence precedes essence.”

These comments could be seen as

pure speculation on the relationship of the philosophy

to the arts. Nevertheless it was Heidegger who defined

a philosophical relationship to the arts that Sartre

appropriated. This excerpt does not specifically talk

about the production of the arts as proof of authentic

existence. However when you read the text it seems that

the ideology of the artist fits perfectly into Heidegger’s

theory of authentic existence:

“The root of man’s

anxieties is his intensity to feel and know that he

exists... and although his fate is to die, he can triumph

over his anguish that the whole is meaningless, by inventing

purposes and projects, which will put meaning upon himself

and upon the world of objects: all meaningless otherwise

and in themselves. There is no reason why man should

do this apart from gaining the authentic knowledge that

he exists: but this is exactly his desire. Not many

are capable of thus authenticating their existence.”

15

Kierkergaard (who also influenced

Sartre in terms of existential art) commented on the

relationship of art and existence. He thought that anyone

who was not either religious or an artist must have

been a fool. It is the comparison between religion and

art that highlights the importance of art. Religion

allows the individual no concern about the meaning of

existence and the other is perhaps concerned with illustrating

our existence consciously or unconsciously, thus providing

a focus.

The relationship of art to existentialism

could be discussed in a purely theoretical term for

the entire length of this dissertation. It is unfortunate

there is not space for an in-depth review of the role

art plays purely in a theoretical sense. The discussion

of existentialism above must be remembered to be very

limited, not only in the depth of the investigation,

but also in the date the text was written as existentialism

evolved through the following decade paticularly in

its political stance. I have tried to analysed texts

very close to the post war period in the hope of corresponding

the date of the works to the depth of existentialism,

I think I have superficially proved that a relationship

exists between existentialism and the arts.

History has been quick to associate

this period of work with the philosophy of existentialism

and it is only through the following investigation that

we shall find out if history is justified.

Investigative Problems

The following investigation presents

many problems that have to be broken down before we

can genuinely make assumptions about the artists relation

to existentialism.

How correct is it to call an artist

an existential artist?

It is difficult to distinguish, in

light of the French post war mood, what was promotion

of fashionable existentialism and what was perhaps the

more genuine embodiment of an individual's feeling or

the mood of the genre.

It is important to point out at

this stage that calling an artist existential is insensitive

to the artists concerns. It is perhaps a statement that

fails to consider all aspects of an artist’s work;

I have primarily tried to ascertain whether some form

of relationship did exist within the artist’s

work. It is only through this detailed examination that

we shall eventually understand the extent to which existentialism

affected the artists.

Is it correct to call the artists

work representations of the existential philosophy?

For example: If you produce art that

abides to the ideals of existentialism, you are not

embodying true feelings about yourself. You are only

producing work that promotes a philosophy; in consciously

representing that philosophy it would be difficult to

encapsulate more than one philosophical ideal genuinely.

Each work would be singular in its content and one dimensional

as its objective would not be a truthful concern of

the artist. It would merely be a weak representation

of the existential philosophy and a weak artwork, neither

genuine in either genre. Ths only art we could define,

as being existential without concern for pigeon holing

the artist, would be art that used existentialism as

its conscious generator for production.

A specific example would be to promote

one aspect of the existential philosophy in a work of

art, e.g. the isolation of man and his anguish because

of this isolation. If I represented this notion it would

show us how isolated man was within the world. However,

if I tried to show how isolated I was, I would be dealing

with true feelings that attain themselves to me, yet

also refer to existentialism at the same time, this

is the more genuine relationship. These feelings can

be used as reflections of existentialism, but not representations

of the philosophy. If this occurs the artist has made

a genuine reflection of that philosophy, albeit in hindsight.

16

There are many artists who I think

have chosen the easier path of depicting existentialism

(perhaps through narrative or style) than there have

been representations of individual expression about

reality that mirrors existentialism.

Examining the artists would show

us the artists who were representing over depicting

and eventually reveal the common aspects these artists

have. The outcome of that commonality would reveal the

genuine relationship between art and existentialism.

Once we have discovered this point we can examine relationships

that are not limited to existentialism or post war Paris

and are concerned solely in the production of the arts.

First a broad investigation into

the connection between existential artists’ works

is essential to reveal the true elements of the origin

of their work that is commonly captivating. Was it the

era, the artists’ frailty, or was it existentialism

(despite my hypothesis) itself that drove these artists

to produce compositions that were so close to mirroring

human existence?

Tate: Paris Post war - Art

and Existentialism 1945-55

In 1993 the Tate gallery held an

exhibition entitled “Paris Post War- Art And Existentialism

1945-55” and it is from this exhibition that I

have chosen to investigate the artists’ link to

existentialism. Historically this exhibition brought

together a group of artists that represent a forgotten

era in the development of the French art scene.

The choice for the artists supposedly

within the exhibition was an attempt to build a more

in depth investigation on a broader exhibition at the

Barbican Centre: “Aftermath: France 1945-54.”

The reason I have chosen to use

the artists from this exhibition is due to the difficulty

in ascribing an artist to the philosophy of existentialism

and to cut down on the over long text that I would need

to justify these artists relation to existentialism.

We can never be certain of artists'

intentions; the justification for a choice of an artist

is perhaps more hearsay than fact.

Due to the length of this thesis,

the investigation into a few artists in depth would

reveal more relevant information, than an investigation

over a broad topic area, although the artists I choose

shall not be without justification. The exhibition organiser

cannot be trusted to make a truly objective decision

without the commercial worry of gaining a large enough

audience; we must examine the justification for the

inclusion of each artist before we can use them. For

example: the inclusion of Picasso within this exhibition

seems to me to be a token commercial offering, that

immediately questions the motives of the other artist's

inclusion within the exhibition. (See fig.1)

The Artists

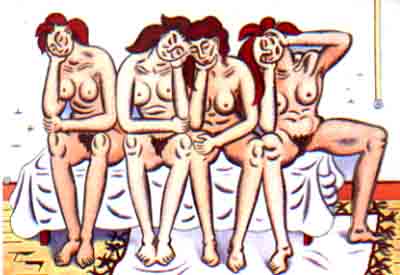

The other artists in the Tate exhibition

are: Antonin Artaud, Jean DuBuffet, Alberto Giacometti,

Jean Fautrier, Wols, Bram van Velde, Jean Helion, Henri

Michaux, Germaine Richier and Francis Gruber. (See

fig.2)

It is in the following text that

we need to exclude the artists who do not need further

investigation into their motives. To me art has to encapsulate

more than an element of the existential philosophy to

be associated as a link, the work should deny singular

comparison to the philosophy and encompasses elements

that refused to be defined in words thus becoming an

equal to existentialism, due to the similarity generated

by a harmony of ideals.

A lot of these artists did have

a personal relationship with existentialism perhaps

directly or indirectly: They may have been involved

within the existential social scene, or may have had

a direct involvement with existentialism, but there

are questions that still remain to be answered; What

is the commonality between these artists and in terms

of representing existentialism how genuine are they?

Jean Fautrier made representations

of hostages that were based on the wartime torture and

summary executions of prisoners, which he heard every

night from his living quarters. (See fig.3) They were

seen as extraordinary in their production. The paintings

were layered very thickly without direct concern for

realism. In this way they were images never seen before,

paintings that broke down the rules of aesthetics know

at that time. However, I feel that these images and

the motifs behind representing these images can only

be superficially existential. The most prominent element

of Fautrier’s work that could be deemed existential

is his use of his medium, due to the “newness”

of the approach. The narrative within Fautrier’s

work is too specific to be concerned with a higher element

of existence within the grand sphere of things.

17

Dubuffet made scenes of urban and

domestic life in a consciously naive style. (See fig.4)

Dubuffet appears to be more consciously aware of existentialism

than Fautrier and his narratives suggest a wider representation

of existence. DuBuffet announced he was a self-confessed

convert to existentialism- the critics noticed his original

approach and linked it to the new existential literature.

Dubuffet’s work in this context appears to be

ascribed to existentialism due to its style rather than

the content and depiction of his work. Dubuffet thought

“Art should go to the roots

of mental activity, where thought is close to its birth”

18

This compares directly to the breakdown

of mans thought within existentialism. He investigated

this notion by purchasing and studying art by schizophrenic

artists and copying their naive style.

These are elements of Dubuffets work

that could be defined as concerned with existential

ideals, however I feel that an in-depth investigation

into his work would reveal more about arts relationship

to society than Dubuffets artistic relationship to existentialism.

It seems to me that he adopted the philosophy considering

the fashion of the day. If it were something that his

beliefs originally paralleled, he wouldn’t have

felt the need to announce that he had adopted the philosophy.

It seems that in having done this his work cannot be

taken as genuine representations of his own art that

reflects existentialism. There are more aspects of this

work that are concerned purely with the method of production

of art, than there are that share the concerns of existentialism.

Jean Helion’s work shows a similarity in its concerns,

it also comments on art more than existence.

Helion produced paintings that were

primarily concerned with abstraction, his pre-war work

was similar to Mondrian’s hard-edged abstraction,

and it was the change of direction in his post-war work

that caused a stir. The work consisted of abstracted

forms that were imposed on figures and it seems now

that Helion is remembered for his attacks on the conventions

of art primarily within the hierarchy of abstraction,

than for his work. (See fig.5)

His inclusion within the Tate exhibition

I think is primarily due to the paintings resonance

of the 40’s and 50’s. At first glance the

paintings’ seem to be purely aesthetic, but after

further investigation the paintings reveal a narrative

that could be associated with existential fiction. The

figures in the plays of Beckett have a particular similarity

to Helion’s figures; they both exist in mediocre

yet somewhat unusual and disturbing situations. In Helion’s

words his narratives concern themselves with

“The extraordinary within

the banal. The mystery of ordinary things.” 19

(See fig.5)

The themes occurring within Helion’s

work also relates to a depraved society, the simple

things like loaves of bread, become symbols of post

war poverty and destitution. (See fig.6)

The figures appear to be alienated and living in isolation

oblivious of each other’s existence. (See

fig.5) These narratives reflect deeply with

the social condition that existed and created existentialisms’

popularity, however there is no direct link to existentialism

outside of the similarity between these narratives.

Helion’s work was symbolist in a surreal manner

of the condition he saw existing in post-war France.

Sartre discarded the notion of surrealism as having:

“A preoccupation with the

unconscious and not the totality of man.” 20

This provides a key to Helion’s

relationship to his depiction of existence. I think

Helion was concerned with the unconscious human condition

of the post-war era, but not in the depiction of the

totality of mans’ existence that existentialism

attempted to describe. Helion does not present himself

as having a multi-layered relationship to existentialism.

Henri Michaux produced a series

of paintings in an intense period of activity after

his wife died. (See fig.7) To Michaux

his experience of pain and suffering was the key to

the production of his art.

“It is through pain and

other extreme states that the individual can most effectively

break through the protective armour of conventional

behaviour, through to intensely personal primordial

mental states.” 21

Francis Bacon commented on Michaux’s

use of mark:

“I think Michaux is a

very intelligent man and conscious man, who is aware

of exactly the situation he is in. I think that he has

made the best free marks that have ever been made, it

is more factual; it suggests more. His paintings have

always been about delayed ways of remaking the human

image, through a mark which is totally outside an illustrational

mark but yet always conveys you back to the human image.”

22

Through Michaux’s image you

experience an image or mark that as Bacon describes

as unconventional. It means nothing, yet aspects of

it revert you back to the image of human physical appearance.

It seems that Michaux’s images connect with the

ideals that existentialism is associated with. A meaningless

sphere of existence (existentialism) / meaningless marks,

(Michaux) which compares to Human existence (existentialism)

/ the human image (Michaux). I think that this similarity

exists as an equality of ideal, not due to the period,

but due to Michaux. The link between existentialism

and Michaux would certainly benefit from further investigation.

A similar artist, whom I also feel

would benefit from further investigation, is Wols. 23

But unlike other artists we have

already assessed, he did not produce his work in conscious

reference to the history of painting or any other concept;

his images were much more genuine:

“My pictures are

not a revolt against anything, in spite of misery, poverty

and the fear of becoming blind one day, I love life.”

24

(See fig.8)

In the second half of this quotation

Wols reveals his concerns with his existence. He was

an alcoholic, who died prematurely in 1951, he found

release from his life in nature:

“It made me forget about

human pretensions, invited me to turn my back on the

chaos of our goings-on, showed me eternity.” 25(See

fig.8 a] )

Wols images appear to be microscopic

structures of life seen under a microscope, or distant

planets seen from a telescope. (See fig.8 b]

) It was Sartre himself who recorded that

“Wols is seeing the Earth

with inhuman eyes, he visualises our universal horror

of being in the world.” 26

(See fig.8 c])

Sartre made comparisons between

his existential novel ‘Nausea’ and Wols’

alarm at the world. Nausea’s main character continually

writes in his diary about the changes he sees occurring

around him in the “World of objects” and

the nausea he experiences from the objects that become

increasingly alien. Wols attempt to see the world through

different eyes was almost an attempt at perceiving our

world objectively. The works are almost like the creation

of another world and existence, that is no less believable

or absurd than our existence. It is when the individual

is confronted with this fact in comparison to these

images that the question of our existence comes to the

forefront of our minds. Wols compares directly to the

existential perception of the world. He encapsulates

the existential philosophy within his work and at the

same time investigates places existentialism does not

touch.

It is this shared sensibility between

Wols and Michaux- the knowledge and expression of perceiving

the world through human eyes that is expressed more

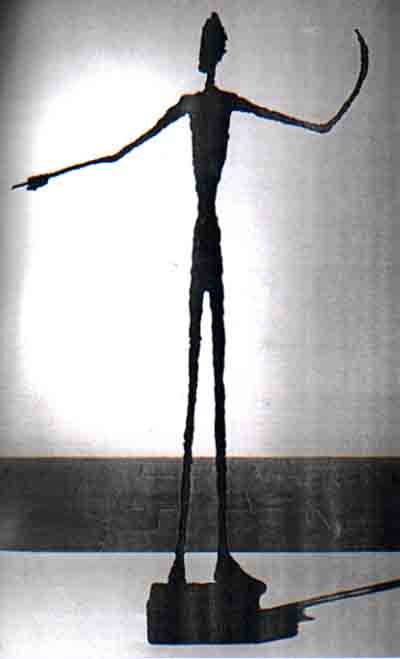

solidly in the work of Giacometti. Giacometti does not

need to be justified as an existential artist, as he

has been unavoidably associated with existentialism

and his work has been termed as representations of “Existential

man.”

Commonality

What is the commonality between

these artist’s? Most of these artists were conciously

or unconciously responding to the effects of the war

on their way of life, although some were not consciously

doing this, like contemporary artists today are not

consciously representing the onset of the millennium,

however whatever affects society in its outlook, also

affect its individuals indirectly. I think the ascribing

of some of these artists to be existential after investigation

is incorrect, as they were responding to their environment

not the philosophy, the term existential is an easy

way of pigeon holing a group of artists that refused

to be defined within a group. Some of the artists' refuse

such a black or white decision about their involvement

to the philosophy, the true commonality between these

artists in reference to existentialism is the individuality

of approach these artists had, more than any conscious

individual representation of the philosophy.

“Non-style, has itself

become a style” 27

Some of the artists have been deemed

existential due to their chosen isolation and the affect

this had on their activity. Perhaps one of the strongest

icons within existential literature was the image of

the “outsider”. The outsider gained a visceral

view of life and society due to their isolation and

their ability to observe more objectively than the involved

individual. However when this is applied to the arts

I feel it becomes a cliché more than proof of

an individuals existential motives.

“The outsider may be an

artist, but the artist is not necessarily an outsider.”

28

Further Study

I think the artists who need further

investigation are Giacometti, Wols and Michaux. (See

fig.9) Jean Helion presents an interesting representation

of the philosophy that could be seen as more literal

interpretations, however I feel his works pale in the

comparison to the perceived world of Wols and Giacometti.

The other artists who I have discussed in this text

are perhaps artists that embodied the scene of existentialism

and may have even been worth investigating in their

relation to existentialism, however I feel that their

work was not strong enough to justify investigation,

or their work was concerned with other ideals that present

themselves more readily. These artists are: Gruber,

DuBuffet and Fautrier.

Other artists I have not even attempted

to include, I feel would take a large proportion of

this essay to justify their inclusion and due to exactly

this fact they do not present themselves as being particularly

concerned with the ideals between art and existentialism:

Artaud, Picasso, Richier and Van Velde. (Velde was linked

to existentialism more than the category I have placed

him defines; however his work denies a formal interpretation)

It is here that we meet several points that must be

assessed before we can continue to discuss the links

between existentialism and art.

Now we have found genuine artists

that reflect ideals of existentialism in their work,

we can gain a more rounded view of existentialism’s

relation to art. However, we must remember to only reflect

between the relationship of art and existentialism.

Giacometti

The painter and sculptor- Alberto

Giacometti had undeniable links within the “Existential

scene”. Sartre and Genet, who both wrote literary

works about him, embraced his work: Sartre with “The

quest for the absolute” and Genet with “The

studio of Alberto Giacometti”.

Sartre also wrote about Wols work

and it is surprising that only Sartre identified these

artists out of the eleven on an existential level. It

is perhaps the link between Wols, Giacometti and Michaux

that needs further investigation to see what shared

relationship these artists hold toward existentialism,

it is the discovery of this association that will perhaps

reveal the genuine relationship of art to existentialism

or the genuine representation of existence within art.

Is it true that because of an artist’s

personal relationship to the philosophy, the output

of their work can be called existential in a philosophical

sense? Does this involvement mean that Giacometti was

an exponent of the existential philosophy? Or was he

an artist merely representing his vision? We cannot

be sure what his objectives were which makes the involvement

of Giacometti a key relationship to the breakdown of

the artist's relationship to existentialism, or the

genuine representation of existence within art.

|

Part II - Giacometti and Existentialism |

“Why do we create?

Michaux said: ‘To

get out of the chaos’

Genet said: ‘To

be loved’

Nabakov said: ‘To

drive back the beast’ “

- From the film ‘The

sexual life of the Belgians.’

Part II - GIACOMETTI

AND EXISTENTIALISM

Introduction

In an interview with Francis Bacon,

David Sylvester talked about the tendencies that occur

when interpreting an artist’s work. In particular

Giacometti’s figures, which have been interpreted

as “existential man”, something that Giacometti

found crass. 29

Giacometti always emphasised that

his work was not concerned with existentialism, 30

however this does not mean that a relationship did not

exist: directly or indirectly.

Was Giacometti work just the representation

of existential philosophy? Or was he representing his

existence? Can Giacometti's work be used as a truthful

reflection of existentialism?

All of these points of investigation

can only be answered by looking in-depth at Giacometti’s

character, then comparing him side by side to the production

of his work and the representations that art reveals

to us. It is only through this examination that we will

discover if Giacometti is truthful to himself or existentialism,

and at the same time find out if Giacometti’s

art can be used to enlighten existentialism. Could it

be that to call Giacometti’s figures existential

was perhaps a sweeping statement, yet it contained an

element of truth?

The link between Giacometti and

existentialism can be traced back to Jean Paul Sartre.

He wrote about Giacometti in his texts as an example

of an artist authenticating their existence.

However the style of existential

art or art that defined itself as existential was a

contradiction.

“Sartre offered an implicit

call to artists to make art without preconceptions;

to define themselves.” 31

So from Sartre’s point of view,

artists should not make art about existentialism, they

should make art about their own existence, perhaps using

existentialism as a tool to unlock the representation

of existence. However this statement cannot be taken

as the literal truth,

“Sartre approaches art

with an open mind, but seeks always to fit his findings

into the philosophical scheme of things.” 32

So even though Sartre called on

artists to make work about themselves, he would still

fit their work in his texts into his philosophy, when

it was not necessarily concerned with existentialism.

It is from the discovery of this point that we understand

why the intentions of the artists of the post-war period

have become so confused with existentialism.

Giacometti

Giacometti first rose to prominence

in the 20’s it was here that he was involved within

the surrealist movement. However it was during the late

30’s he became convinced that surrealism was not

satisfying his concerns and he showed a desire to return

to what he regarded as

“Contemporary sculptures

real problem- the recreation of the human face”.

33

For Giacometti’s peers within

the surrealist movement, it was quite a shocking transition

from surrealism to the life model. (See fig.10) One

of his colleagues commented “Everyone knows what

a head is” but in Giacometti’s opinion no

one had succeeded in representing a valid human appearance,

the whole thing had to be started again from scratch.

34 It was the desire to begin again that earmarked the

work of the French post war scene.

If we take Sartre to be the advocate

for existentialism, particularly in his relationship

with Giacometti, we can learn a lot from the documents

about their relationship. Sartre and Giacometti were

friends and Sartre promoted Giacometti, not directly

as an existential artist, but the essays he wrote about

Giacometti’s work had a definite existential flavour.

Giacometti and Sartre formally met

in 1941 during the occupation:

“There was a deep bond

of understanding between him and Sartre, they had both

staked everything on one obsession. Literature in Sartre’s

case, art in Giacometti’s and it was hard to decide

which one of them was more fanatical”. 35

This excerpt from the memoirs of

Sartre’s partner- Simone de Beauvoir hints at

the equality of the relationship between both Sartre

and Giacometti, this could also be a clue to the true

equality of the relationship between existentialism

and Giacometti.

Giacomettis Concerns

Giacometti seemed to suffer from

an irrepressible form of agoraphobia; in fact he seemed

to have many concerns that interfered with his everyday

life and ultimately fed through to his artwork. His

fears about spaces and other beings are perhaps two

concerns that lead us directly to his paintings and

sculptures.

“His real concern with

his work was to defend himself against the infinite

and terrifying emptiness of space”. 36

It was this attraction and repulsion

to space that created one of his motives for creating

his works. 37 (See

fig. 12)

Whenever he painted or sculpted

a figure he always asked the sitter to look him directly

in the eye. Giacometti thought that the only sign of

existence in the physical make-up of the figure lay

in the eyes. This difference between existence and a

dead object needed to be affirmed by Giacometti. He

needed to prove that others existed and record it within

his work. (See fig.12) James Lord (said

this was exactly why he worked the way he did)

“Alberto was working to

demonstrate that he was alive.” 38

“People seem like ants,

like men who come and go in the street...a completely

foreign species, mechanical.” 39

Giacometti expresses here the alienating

experience that occurs when you are surrounded by human

life and swamped by what seems like faces without meaning

and purpose; the bare reality of human existence. This

compares directly to the isolation of what Sartre called

‘Nothingness’ in which

"human reality carries with

itself the nothing which separates it’s present

from all the past.” 40

Giacometti himself described his

perception of people during one period of his life.

“I started seeing living

heads within the void, the head that I was watching

became closed off and immobile in an instant, it was

no longer a living head but an object- something alive

and dead simultaneously. I cried out in terror, as if

I were entering a world never seen before. All living

beings were dead, in the metro, in the restaurant, with

my friends.” 41

For Giacometti

“Seeing was the equivalent

of being”42

You sense he is attempting to observe

something beyond the shallow depths of human identity.

Instilling with great intensity the living human face

that represents us all. (See fig.12) When we consider

his paintings, drawings and sculptures we can see his

solid vision of attempting to pin down the living form

in the medium of his choice. (See fig.13)

The forms seem to be in direct relationship with the

space around them, like Giacometti’s concerns

about open spaces.

Giacometti’s Work

Giacometti insisted that he rendered

what he saw, he had no other motive. It was his attempt

to record that total vision and represent his fears

about existence that perhaps echo’s the existential

philosophy. Giacometti represents a primordial aspect

of viewing or observing, recording the rawness, the

bones of existence.

“The existent individual

will be he who has the intensity of feeling because

he is in contact with something outside of himself.”

43

This point is taken from a discussion

on the roots of existentialism; it parallels Giacometti’s

character and his comments about feeling outside of

society or beyond the social situation he was within.

It was this contact with something outside of himself

that made him try and record his vision of a reality

that was detached from the interference of the human

eye and brain. His task represents the attempt to peel

back the layers of observed human existence, to find

the truth behind reality. This was the same objective

as the existential writers. They reduced existence to

bare necessity, to attempt to reveal the significance

of existence, or the poignant moments of life.

Giacometti’s attitude to his

work can also be seen as having links with existentialism.

44

The

“Forced labour”

45

as Giacometti called it, the squalid

state of his studio and working conditions created an

image of the driven artist who despite fame, abandons

material comforts for the quest of his goal. (See

fig.14)

“Giacometti did not give

a damn for success or reputation or money; all he wanted

was to carry through his own ideals”. 46

Giacometti was also fuelled by his

failure in the quest for creating his vision. He would

often destroy his sculptures;

”Whatever he did by day,

he smashed up at night and vice versa, one day he piled

all the sculptures in his studio onto a handcart and

went off and tipped them into the Seine.” 47

Sartre associated the sculptures

that Giacometti destroyed with transiency:

“Never was substance less

eternal, more fragile, more nearly human.” 48

(See fig.15)

This fact alone leads us to believe

that perhaps Sartre thought Giacometti had made a modern

synthesis of modern man with values that parralled the

existential ideal of existence. His observed perception

of human existence and the unexplainable finite existence

hints at the existential ideology, this is one explanation

of Giacometti’s destruction of his figures. However,

I feel Sartre’s interpretation of this is somewhat

poetic and he is fitting Giacometti’s nature into

his philosophical scheme of things. This was Giacometti’s

method; he was striving for the unattainable. Giacometti

destroyed his work if it failed in its objectives, which

it invariably did. 49

It was the paradox of continual acknowledged

failure that kept Giacometti striving for unattainable

success. He said of his method:

“If I knew how to make

one, I would make them by the thousands.” 50

However we know this was not true,

Giacometti’s failure in a task that was unattainable

only spurred him on to see how close he could get to

recording reality truthfully. The prospect of making

a work that was closer to his goal also made him strive

forth. For Giacometti failure was as important as success

and as the years went by, the boundaries between failure

and success became increasingly blurred.

“I do not know whether

I work in order to make something or in order to know

why I cannot make what I would like to make.”

51

Giacometti knew he was trying to

achieve the unachievable; yet he would fall short way

above the place where other artists would deem “Unachievable”.

For Giacometti it was not the destination but the journey

that was important.

Simone de Beauvoir describes Giacometti’s

working methods better than I.

“It was impossible to predict

whether he would “Wring sculptures neck”

or fail in his attempt to master space; but his struggling

endeavours were per se more exciting than most other

men’s successes.” 52

Assesing this information I feel

Giacometti’s working methods were not linked to

the existential philosophy. They were linked to Giacometti’s

need to produce his work.

Giacometti and Existentialism

So, how closely can we use the term

Giacometti and existentialism? There are too many coincidences

between Giacometti’s production of art and the

existential philosophy to say that the two are not linked.

However, we have not defined in what way there is a

link.

Sartre was particularly struck by

Giacometti’s attempt to view the truth behind

reality; it was something he had been striving to do

also;

“Giacometti’s attitude

was comparable to that of the phenomenologists.“

53

This quote provides a clue to the

relationship of Giacometti’s art and existentialism.

Phenomenology is a scientific branch

of psychology that concerns itself with the study of

perceptual facilities. It rejects abstract reasoning

in favour of observation and description. It was used

to describe the world of objects within which the consciousness

perceives itself. Phenomenology was the basis of part

of the existential philosophy. It was used in reference

to perceiving existence and the world around us when

looking in a special way i.e. the nose is always in

the line of vision, but rarely recorded.

Phenomenology stated that there

was no objectivity, as perception depended on a pre

existent element of choice, which determines the form

in which we perceive every phenomenon of which we become

aware. 54

For instance: with this diagram you

will either see a black Maltese cross or a white flower.

The tendencies to perceive either one of these things

could mean that you were military or horticultural minded.

What is perceived is a tendency toward a certain goal

or purpose. However, the existential phenomenologists

attempted to describe things as they existed for other

people removed from them. For instance they would attempt

to describe things without any pre-existent influence

or subjectivity coming between them, and the description

of the things around them.

This is perhaps a close link between

Giacometti and existentialism; his intense vision to

illuminate reality in terms of a synthesis compares

directly to the existential use of phenomenology.

The cross-referencing of Giacometti's

observation and phenomenology shows us a close link

between Giacometti and existentialism. So was Giacometti

using some form of existential phenomenology in his

art or representing his own vision? I don’t think

the answer is as black or white as I have suggested.

I think Giacometti can be used to illuminate existential

phenomenology and the relationship to observation, there

is a direct link between the two, however I dont think

it is a conscious link. Giacometti was trying to represent

what he saw due to concerns about his life; he needed

to represent his vision to record his reality, as he

was not always contained within our “Sphere of

existence”.

He was not using phenomenology within

his art, just representing his concerns, however this

does not mean that he cannot be used to examine phenomenology

within existentialism. This is perhaps the strongest

link between existentialism and art, both ways of interpreting

the real world.

“Ponge and Dubuffet were

articulating important ideas about post war art long

before Sartre’s first exhibition preface of 1946.

Artists and writers were going back for phenomenological

inspiration to the same sources as Sartre himself, without

the philosophies mediation” 55

At the beginning of this section

I posed the question “Was Giacometti just the

representation of the existential philosophy or representing

his existence?” I think from the evidence I have

presented in the information above we can decide that

Giacometti was truthful to himself he was not representing

existentialism. This is shown by the equality of Giacometti

and Sartre’s relationship, also the way that Giacometti’s

concerns and fears filtered directly into his work.

(These fears were genuine and were not the product of

a relationship to existentialism.) In the bigger picture

these concerns perhaps paralleled the notions that existentialism

discussed; for example the isolation of man surrounded

in meaningless space.

So, at this level there is a parallel

between the core of Giacometti’s persona and the

ideology of existentialism. Another fact that highlights

the equality of the relationship was Sartre’s

admiration for Giacometti’s attempt to view the

truth behind reality; this was something Sartre had

also attempted from a youth. It is Sartre’s use

of phenomenology and Giacometti’s attempt to render

what he saw (Which we have found parallels phenomenology)

that leads us to believe that Giacometti can be seen

as a truthful reflection of existentialism.

I think Giacometti was not an existentialist,

he shared the same outlook on life and he asked the

same questions the existentialists asked. Yet he chose

to represent life exactly as he saw it, without abiding

to the existential philosophy. Giacometti does not recreate.

He just creates in an existential way. I think Sartre

and Giacometti had independently evolved a similar way

of understanding existence.

Are Giacometti’s figures existential?

His figures do not relate directly to existentialism,

which makes it more wrong to call them existential than

it is correct. Therefore we cannot call them definitively

existential, but for a greater understanding of the

method of representing percieved existence within art,

Giacometti can certainly be used as a study.

For a final examination of the relationship

between existentialism and Giacometti, it would be interesting

to superficially compare Giacometti to an artist who

did use existentialism directly.

Bernard Buffet was a figurative artist,

of the same period as Giacometti; he was very successful

and perhaps cashed in on the popularity of existentialism

and its style. Buffet created

“Literal interpretations

of the gloomier and more superficial aspects of Sartre’s

existentialist philosophy.” 56

(See fig.16)

If we make a visual comparison between

Giacometti and Buffet, we can perhaps see the difference

in depths of engagement between the two artists. Perhaps

this is due to the difference in the artist’s

objectives? Depicting existentialism is like reviewing

a book so the reader doesn’t have to read the

whole text. It falls short of the concerns the philosophy

has to begin with, as it has a definite purpose.

Looking at the overall picture,

I think we can gain a clearer understanding of existentialism

when we consider Giacometti’s work; as long as

we acknowledge the limitations and that his work can

be used as a reflection (Not a depiction) of the same

concerns that existentialism is associated to. By looking

at Giacometti we can obtain a different view of existentialism,

that is strong, and an equal to Sartre. Giacometti represents

images of substance, rather than being a second to existentialism

like Buffet. It is that shared understanding of existence

that perhaps links the work of Wols, Giacometti and

Michaux. The commonality between these artists would

perhaps reveal a relationship to the core of existentialism

that can be investigated outside of the post war era.

|

Part III - The Arts and Perception- Existentialism? |

“It’s

as if artworks were re-enacting the process where the

subject becomes painfully into being.”

T.W. Adorno, Aesthetic

Theory

Part III - The

Arts and Perception- Existentialism?

Introduction

Throughout the examination between

Giacometti and existentialism we have discovered that

there are definite links that can be drawn between the

philosophy and the production of art itself, the act

of doing and seeing, but the content of the works can

only be compared to parts of the philosophy, e.g. Giacometti's

figures and the void- being and the separation into

nothingness. (See fig.11) In this section

I hope to investigate beyond that limited relationship,

the symbiosis between a philosophy and the arts is unusual,

the reason existentialism and the arts were so close,

was not only due to the historical events but due to

a shared concern about perceptual reality that art has

always contained, that was focused firmly in the post

war era particularly in reference to existence and the

individual. This concern was reflected equally in philosophy,

literature and the masses.

Existentialism and Contemporary

Influence

The post war era was a flash point

of concern about the fate of man and the individual

purpose. This affected the following decades:

"The practice of

art from world war two to the end of the eighties was

dominated by ideas derived from phenomenology and existentialism.

The post war period attributed to modernism, in the

sense that it claimed that art was capable of reuniting

with some lost essence and art was able, as well, to

release hidden, heretofore unaccomplished potentialities

in the human being" 57

This quote highlights the viability

and existence of ideas associated with the artists we

have chosen outside of post war existentialism.

Wols and Giacometti cannot be compared

to artists outside their era in existential terms, as

existentialism was definitely a philosophy that cannot

transcend its point of creation, as it was firmly rooted

and created within its time. However the shared sensibility

between Giacometti and Wols can be compared to other

artists.

Giacometti produced art that we

have already discussed as relating to phenomenology.

He carefully analysed reality, in an attempt to make

the substance he was working with closer to the living

being he was observing, rather than just an inanimate

object.

Wols observed nature and created

visions that are so far removed from normal perception,

it feels as if we are observing through the eyes of

an alien or animal, this makes us immediately question

our vision of reality. It is the empathy of a perception

detached from our own that reverts us to questioning

our 'sphere of existence'. It is this "phenomenology

of perception" that Giacometti and Wols represent

within their work almost like a tool to questioning

or recording their perceived world.

It is the perception of reality

that is an artist's primary concern, and that concern

seems to be able to impart questions of existence without

the barriers of words or politics, due to its direct

submergence within the gaze of the viewer, it is this

same gaze that tells the viewer about the reality around

them.

"In art we experience

a wholeness derived elsewhere. The mirror of art provides

a vision of the whole which direct empirical observation

cannot give." 58

The use of perception within art

shares an ideal with existentialism, yet it is stronger

within the arts than in existentialism and any relationship

between the two would develop primarily from the arts.

This means that an investigation into the relationship

of artist's observation and what is perceived, outside

of the existential era would be legitimate as it is

a concern that has its strength and originates from

within the arts- before and after the development of

existentialism.

Cezanne To Arikha- Existential

perception not limited to existentialism.

In this section I hope to superficially

demonstrate the existence of artists dealing with perception

before and after existentialism, art that historically

seems to have made possible due to existentialism, however

the art we have found to be genuine existed already

outside of the philosophy as a natural confrontation

with perceived reality. Not as a product based on discourses

about phenomenology.

The post war period points back

to Cezanne as the father of phenomenological perception.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote about Cezanne in his book

"The Phenomenology Of Perception". (He wrote

about artists in relation to existentialism before Sartre's

texts on Wols and Giacometti)

"Painting was his

world and his existence, anxiety was the basis of his

character, Cezanne proved to be the model of asceticism,

his life work doomed to failure, as a saint is doomed

to imperfection. Cezanne wished to paint a primordial

world with an emphasis on the immediate translation

of sensation." 59

(See fig.17)

This shows a similarity to Giacometti's

'existential graft of constant failure, at the attempt

of recording the translation of what is truly perceived.

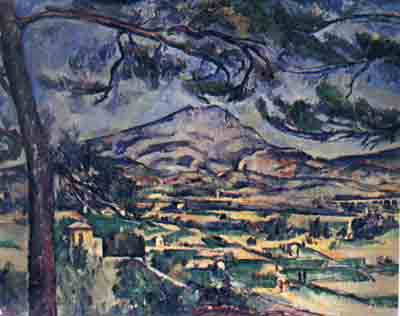

Cezanne painted the Mont Ste Victoire

time and time again without conceiving one version as

the definite representation. (See fig.18) His

repeated effort to record what he perceived failed repeatedly,

yet he still tried to translate what he saw before him

directly into paint.

"He was a self made

painter, one not presented with facility but a man who

has to painfully uncover his talent and find the means

to give shape to his ideals." 60

It is the combination of several

points that leads Cezanne to paint in the way that has

been described, his devotion to painting and his concerns

fed into his work just like it did in Giacometti's.

It seems that the similarity between Cezanne and Giacometti

perhaps provides the mould for perceptual art. There

needs to be a confrontation with reality something that

makes the artist have a heightened awareness of his

situation directly with in the world around him.

"He had indeed a relationship

with the acceptance of the validity and truth of immediate

perception. His grappling with the intensity of his

sensational impressions was one source of his creative

agony." 61

Just like Giacometti Cezanne speaks

of instilling what is before him with concentrated observation

that is doomed to failure:

"Painting is not only to

copy the object, it is to seize a harmony between numerous

relations." 62

In this text I have referred Giacometti

to Cezanne as a point of reference, however the relationship

existed primarily in reverse. Giacometti was a great

admirer of Cezanne:

"What motivated Giacometti

to develop was Cezanne’s practice of requiring

many posing sessions for a portrait, his persistent

dissatisfaction with results and his belief that a work

of art could never be really finished." 63

Here we see the influence of Cezanne

to Giacometti and it is perhaps an influence that should

resonates among all artists working in terms of perception.

There is a commonalty of concern shown between these

artists that represent art dealing with existence in

the only way it can, through perception.

At the other end of this century

the artist Avigdor Arikha also showed a similarity of

concern. He painted still life through the seventies

after rejecting abstraction. (See fig.19)

Just like Ponty and Giacometti guide us toward Cezanne,

Samuel Beckett points us toward Arikha. 64

Arikha rejected abstraction, as

he had not linked "the act of painting to the

fact of seeing" 65

His work represents the process

of observing and conscious examination of the method

of production. "To draw reality is to examine

thought itself" 66

It is the process of drawing Arikha

lays bare for us as an examination of what is perceived.

(See fig.20)

"Arikha has inverted the statement

of conventional realism: 'this is what I see' becomes

'is this what I see?'

The observation and recording process

is enough in itself to confront questions of existence:

"Since I regard art

as the echo of being in its most elemental sense, I

see the role of observation subject to a sort of igniting

power, it is a search for facts, but one cannot through

that alone, achieve a truly faithful portrait, more

is needed to achieve that, which is much more than just

measuring." 67

It is the instilling of a number

of relationships that leads to something beyond mere

recording and observation.

"His non-alignment

with modern movements and his solitary dedication to

pictorial empiricism links Arikha’s work most

closely to another independent, Alberto Giacometti.

Both after working in modern idiom's surrealism for

Giacometti and abstraction for Arikha- have changed

to an intense involvement with directly perceived reality

and its realisation of its essence in their art."

68 (See fig.21)

This quote highlights the point

I made previously about Giacometti and Cezanne becoming

the mould for existence represented in art via perception.

Existentialism and Perception

It is this link from Cezanne via

Giacometti to Arikha that reveals how perceptual art

that confronts questions of reality consciously existed

separate from existentialism. This highlights how Giacometti

was seen as an existential artist working existentially

when he was in fact only working in the way artists

have been working before and after existentialism. Arikha

shows a very similar life style and concerns as Giacometti,

yet he has not been linked to any form of philosophy

or movement. It is this fact that highlights that Giacometti

could have worked in the way he did without reference

to existentialism, yet it was the conjunction in history

between the arts and existentialism that labeled Giacometti

'existential'

As an artist you cannot avoid coming

into contact with the perception of reality, however

it is the artists who strive to define that perception

of reality that are confronting direct questions about

the relation of the individual to existence. This is

the same ideology that existentialism is based upon;

the individual's action concerning existence.

Existentialism defined the production

of art as proof of authentic existence. The highest

form of artist I have found grouped in the existential

bracket were those individuals that were mainly concerned

with the perception of the world: Giacometti with his

attempts to create a synthesis of the world as an affirmation

of existence through the proof of an artistic record.

Wols perceived nature in the eyes of an alien- as if

he had never seen the world before. These artists show

us that the only way that anything that can be identified

with the term existential can only enter the arts genuinely

through "perception of the world". This confirms

that the other artists like Dubuffet and Helion perhaps

created records of painting history more than genuine

representations of the individual response to existence,

that transcend the philosophy.

However this leaves an enigma: to

refer back to the arts that show a similarity of concern

to existentialism is inadequate, as it is not viable

to relate contemporary thought to an earlier point in

history, as the same contemporary thought resulted as

a direct development from that original point.

Philosophy and the arts are two separate

concerns that to be genuine in either area have to remain

separate. When an event like the war occurs that pushes

the two genres together, the genuine aspects of the

production of art become questionable and difficult

to separate. At the beginning of this essay I intended

to investigate how existence is represented within the

arts. I have found that genuine representations are

made by perception either through direct observation

or perceptions within the viewers mind. The works that

are not associated with making the mind question what

is truly perceived, fail in evoking notions that associate

themselves with the existence of man.

Wols and Michaux shared this relationship

to what is perceived in the mind. Wols alienates the

viewer making him question what he truly sees, Michaux

shows us how the mind can never perceive anything but

itself, as we always transform the object in our sphere

of existence into a purpose, we relate what is around

us to the meaning it has on our life. We revert the

image of man onto meaningless marks

These artists show us we can never

escape our own existence long enough to perceive reality

truthfully. Giacometti seems to have attempted to escape

the unquestioning gaze of a human being, to try and

record what he sees truthfully. This he does instead

of allowing the individual to question what is perceived

(like the art of Wols). Giacometti already questions

what he sees and attempts to record it from the point

where he questions the true perception of everything.

It is as if Giacometti is recording exactly the point

the viewer of Wols work realises. It is here that we

see that the art of Wols, Michaux and Giacometti differs

in their output, yet share the same concern but they

are making different representations at different points

on the same notion of perceived perception. (See

fig.9)

This reveals to us that the genuine

representations of questions of existence from the individual

(In terms of existentialism) can only be made through

the use of perception, perception that exists throughout

this century’s art and is not limited to the Existential

era and therefore not limited to Existentialism.

Conclusion

I feel now assessing this information

that existentialism throughout this dissertation has

not presented a single strong link to the production

of art in the post war era.

There are symbiotic links between

the mode of thought between the arts and the philosophy,

but the link does not genuinely go beyond the mode of

thought. To produce a genuine artwork the artist must

focus his total attention on what is totally perceived

in artistic terms. Any less or differing focus results

in a work that is weak- as it has a purpose, and art

that has genuine concerns does not have a purpose, it

deals with a translation of one element into another.

In this case the translation of perception or sensation

is perhaps the strongest form of conveyance the artist

can achieve.

To refer to this art as existential

I feel is inadequate, existentialism acted as a catalyst

to the production of work concerned with existence,

all different types of work were produced that would

not have normally been concerned with existence, however

it was only the work of artists concerned with perception

that was not totally eclipsed by existentialism.

Ideals associated with existentialism

only exist in the work of artists dealing with the perception

of reality, however the art associated with perceiving

reality has existed before and after the existential

era, so comparisons to existentialism can only genuinely

be made in this time period. Outside of that period,

even though we know that we can relate it to existentialism

it becomes something separate. It is no longer as relevant

to relate it to existentialism, as it is a separate

entity with no direct ties to the past philosophy.

The shared relationship between Wols,

Giacometti and Michaux has allowed us to investigate

perceptual art outside of the post war era. This means

that we can put existentialism’s relationship

to art into perspective, yet at the same time it presents

a loose specification for the production of work, that

records and comments on perception in the strongest

way of representing existence within art.

Another clue to the similarity between

existentialism and the arts is the fact that the artists

were going back and reading phenomlogical texts independently

of the existential writers. This certainly reveals one

reason for the similarity between the concerns of existentialism

and art, it is only history that has perceived phenomenology

originating in existentialism and filtering into the

arts, not the genuine origin of source. The origin of

phenomenology is the only link between the arts and

existentialism, it is the same source we know discuses

notions of perceptual reality and existence. We know

that the recording of perception existed before existentialism

and the philosophy only strengthened its appeal.

It is this point again that highlights

the existence of notions of perception existing before

existentialism and then existentialism is remembered

unjustifiably for creating phenomilogical perception

within the arts. The true elements of phenomilogical

art existed before existentialism and were then strengthened

by the philosophy and made its own. The same appears

to have occurred with Giacometti's production of work.

That strengthening process and existentialism

itself, probably wouldn't have existed if it weren’t

for the war and the affect it had on every individual

and society as a whole. If the situation is strong enough,

society affects the individual in unprecedented ways

and this can be seen in the production of arts in the

post war era. 69

"At the end of the

seventies the transcendelist, phenomilogically orientated

approach which had been dominant for thirty years abruptly

disappeared. Consequently the existential values of

the world war II generation have faded away- the younger

generation (In the western world at least) has never

experienced a situation, in which all the rules are

found inapplicable" 70

It is unfortunate that the quest

to record genuine perception within art has lost its

strength, this art forms what I feel to be the strongest

way an individual can record their individual perception

to existence, it holds important values as perceptual

art transcends language, time and the existence of the

individual who created the work, For as Kierkergaard

said:

"An image is eternal when

its form, its pictorial surface and its content are

perfectly matched" 71

and this is certainly achieved by

the genuine perception of reality.

1.Barbara

Kruger. Art in theory.1992.p1072.

2.Frances

Morris. Paris Post War, Art And Existentialism 1945-55.

1993. p.18

3.John

Strand. Do You Remember The Fifties? Art International,

no.4 Autumn 1988. p.6

4.Antonin

Artaud. Paris Post War, Art and Existentialism 1945-55,

1993.p.181

5.Britt,

D. Modern Art: Impressionisim to Post Modernisim. Boston:

Little Brown, 1989.p234

6.John

Strand. Do You Remember The Fifties? Art International,

no.4 Autumn 1988. p.7

7.Jean-Paul

Sartre. Existentialism And Humanism. 1997 reprint. p26

8.Sarah

Wilson. Paris Post war – Art and Existentialism,

1945-55.1993.p.38

9.Jean-Paul

Sartre. Existentialism And Humanism. 1997 reprint. p28

10.Jean-Paul

Sartre. Existentialism And Humanism. 1997 reprint. p29

11.Jean-Paul

Sartre. Existentialism And Humanism. 1997 reprint. p41

12.Britt,

D. Modern Art: Impressionisim to Post Modernisim. Boston:

Little Brown, 1989p.234

13.Jean-Paul

Sartre. Existentialism And Humanism. 1997 reprint. p42

14.Jean-Paul

Sartre. Existentialism and Humanisim.p.49

15.Martin

Heidegger. Philip Marriet. Intro to Jean-Paul Sartre.

Existentialism And Humanism. 1997 reprint.p.14

16.If

we compare existentialism to religion (As a way of comparing

the expression of a mode of belief within the arts.)

it can show us the different ways existentialism can

be represented within the arts. If an artist represented

scenes of the bible, they would be referring back to

religious texts rather than encompassing the total experience

the individual gains from a mode of belief. This is

the only genuine relationship the individual can have

to representing religion. To refer to the bible is to

recreate and belief in god is not necessary to represent

scenes of the bible, to express the experience of religion

on a personal level is to encompass genuine notions